A Square Supervisor’s Perspective of an Archaeological Excavation

Dr. Terry Eddinger

Before reading this page, I encourage you to begin by first reading "A Student’s Perspective on an Archaeological Excavation" and then come back to this page. The Student’s Perspective page will provide you with a good general overview of life on a dig. This page will focus on the specific duties of a Square Supervisor.

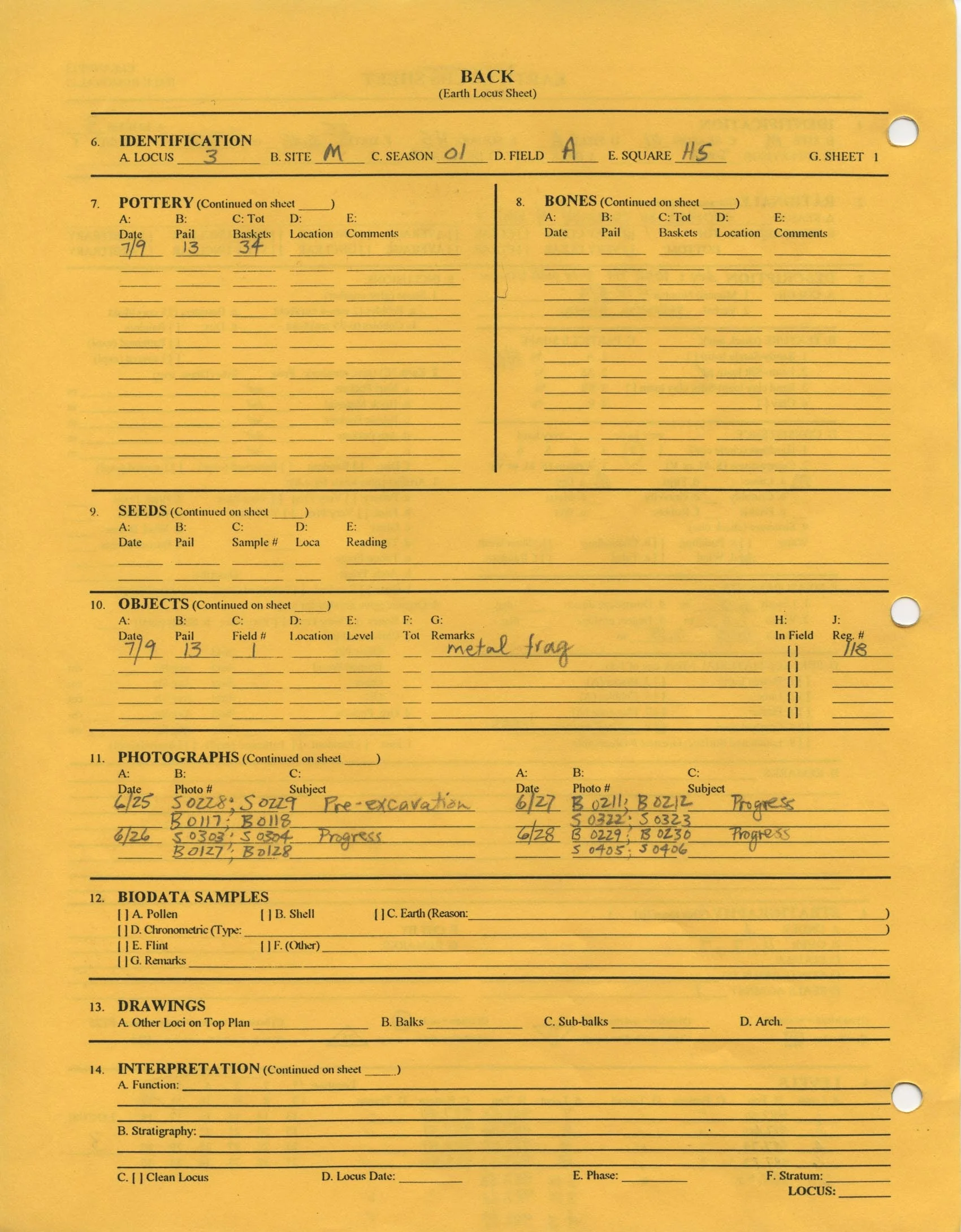

The Locus Sheet

Locus Sheets are the key tools for recording raw data from the excavation of a square. This page explores the basic information one can expect to find recorded on the Locus Sheet.

KRP’s Locus Sheet utilizes both sides of the sheet, which has a total of 14 major sections. Each section is briefly discussed below.

Obverse

- Identification - This section is where one records the basic information—season, site, field, square number, date, locus number, Square Supervisor, etc.

- Rationale - Rationale refers to why one changes loci. Also, one indicates how clear the top and bottom of the locus can be distinguished from surrounding loci.

- Description - The “Description” section is the most detailed of all sections. Here, one records Munsell numbers (for soil color), information on texture and consistency of soil, size of locus, type of surface (if applicable), and the types and amounts of inclusions, such as stones, bones, organic materials, etc. Also, one can make notes about the locus on the “Remarks” lines that could be particularly helpful for interpretation later.

- Stratigraphy - A locus never occurs in isolation. This section is for describing the relationship of the current locus with surrounding loci.

- Levels - Levels refer to the top and bottom elevations at a particular place in a locus. The set of numbers marked “Location” in the bottom right corner is a reference (a chart) for each square meter within a 6 x 6 meter square. Elevations are plotted according to this chart.

Reverse

- Identification - Same information as #1 but on the backside of the page.

- Pottery - Pottery Pail Numbers and dates that correspond to the locus are recorded here. Also, this is the section where one records the total number of gufahs of dirt that were removed while a particular pottery pail was being used. After Pottery Reading, the results are recorded here also.

- Bones - Bone information is recorded here. Bones are controlled by Pottery Pail Numbers. Also, a listing of any identifiable animals from the bones is recorded here.

- Seeds - Information about seeds found in a sample is recorded here, according to the Pottery Pail Number.

- Objects - Objects are artifacts that do not fit into a previous category. Objects are controlled by Pottery Pail Numbers; however, they are also given an object number. All of this information is recorded in the “Objects” section.

- Photographs - Any photograph of the square that has a particular locus visible must be recorded here on the corresponding Locus Sheet. These photos can be Progress Photos, Final Photos, or special photos of objects in situ (in its original place), installations, etc.

- Samples - Sometime one will take a sample (such as soil) from the square for additional analysis. These samples are listed here.

- Drawings - All drawings that illustrate the location of a particular locus are listed here.

- Interpretation - The Interpretation section allows one to state briefly what is happening in the square in terms of the function of the locus. For example, one may state that the locus is a floor of a building, a debris heap, or a storage pit, according to what is appropriate.

That is the Locus Sheet in brief. As one can see, some of the information is recorded at the onset of excavating the locus while other information cannot be recorded until a much later. The Square Supervisor must be diligent and give careful attention to detail in order to correctly and completely record all the available data concerning a locus.

Before the Excavation

Before the excavation begins, the square supervisor is already busy at work. There are three important elements in this pre-excavation stage: 1) getting to know the Field Supervisor, 2) reading everything possible about the site and about the time periods in which the site was occupied, and 3) learning about archaeological methodology. Let’s look at these one at a time.

The first element is getting to know the Field Supervisor. The Field Supervisor is responsible for all the squares in a given area (a Field). For example, Field D at Mudaybi’ had three Squares. Each square has a supervisor that works for the Field Supervisor. An amicable relationship is important here since these two people work closely together in the excavation process. Because the Field Supervisor is responsible for all work in a particular Field and because this person writes the final reports for the Field, the Square Supervisor needs to keep the Field Supervisor informed of all work within the assigned square BEFORE the work takes place. Also, the Field Supervisor maintains the “big picture” of the Field. A discovery in one square may affect the excavation method in another square. Therefore, collaboration is of the utmost importance.

The second element is background knowledge. A Square Supervisor needs to learn as much as possible about the history of the site (and region) and periods of occupation (if possible). Any specialized reading will be helpful. The Excavation Team probably will have a general reading list that will include materials in this area.

The third element is learning about archaeological methodology, especially the system used by the Excavation Team that one is associated with.

The best place to start is the excavation manual used by that particular excavation. Karak Recourses Project uses Excavation Manual, Madaba Plains Project. The Square Supervisor needs to read this manual thoroughly and understand the system before commencing excavation since the manual will contain procedures for recording data. Remember, once data is lost, it’s gone forever—so learn the system!! For most excavations, the Locus Sheet is basis for recording data. For more information about the Locus Sheet, click here. The Square Supervisor will want to study ancient architecture. There are many ways to build a building. A Square Supervisor needs to be able to recognize the different styles of construction. In addition to thinking about vertical construction, i.e. walls, one needs to learn about horizontal construction, that is, surfaces—packed earth, plaster, stone pavement, etc. A Square Supervisor is likely to encounter both of these in the excavation process.

The Square Supervisor will want to study ancient architecture. There are many ways to build a building. A Square Supervisor needs to be able to recognize the different styles of construction. In addition to thinking about vertical construction, i.e. walls, one needs to learn about horizontal construction, that is, surfaces—packed earth, plaster, stone pavement, etc. A Square Supervisor is likely to encounter both of these in the excavation process.

Before the excavation process begins, the Square Supervisor must obtain all the materials needed in the field. The Excavation Team should provide these materials. Items needed include data recording items (such as Locus Sheets, Pottery Pail Tags, Object Tags, graph paper, etc.), tools (meter tape, plumb and line, pencils, erasers, Sharpies, counter, clipboard, extra sting, nails, line level, scale ruler, compass, Munsell charts, etc.), small plastic and paper bags (for bones and objects), Field Notebook, and a copy of the excavation manual. Whew!!! One needs a backpack to carry all that stuff! But all of it is essential for collecting data. Also, the Excavation Team usually provides excavation tools such as picks, trowels, dustpans, gufahs, etc.; however, I suggest the Square Supervisor purchase his/her own Marshalltown 45-5 trowel. (Not having one’s own trowel is like a stigma indicating a neophyte! No archaeologist is complete without a personalized trowel!!) As a side note, I always carry one of those pliers’ tools such as a Leatherman® or a Gerber®. These tools are real handy in the field and are good for anything from cutting tennis balls to put atop rebar stakes to picking up scorpions.

I was fortunate to have a very good assistant to help with much of the preparation work. Assistants are usually college students who have an interest in archaeology. A Square Supervisor does well to recognize the talents of an assistant and put those talents to good use. In 2001, my assistant was very adept at drawing top plans and balks (better than myself) so I encouraged her to do almost all of the drawing for the square.

Beginning of the Excavation

Once the Square Supervisor lugs all that stuff to the site (excavation tools probably will be at the site already), then he/she works with the surveyor and the Field Supervisor to lay out the 6 x 6 meter square (a specific square predetermined by the Excavation Team). Iron rebar stakes mark the corners and carpenter’s string outline the edges. Also, a one meter balk is outlined with string held by rebar stakes on the north and east sides of the square. Next, the Square Team (Square Supervisor, assistant, and local workers) clean off the exposed surface by removing grass and weeds; however, they are careful to leave any stones. Now the square is ready for preliminary photos and the drawing of the initial Top Plan.

Before the actual excavation begins, the Square Supervisor examines the square and, with the Field Supervisor, formulates the “plan of attack” (plan for excavation). While the plan is being made, other preparations are underway such as setting up the sieve, drawing an initial Top Plan, discussing procedures with local workers, preparing Locus Sheets and Pottery Pail Tags, taking initial elevations, etc. Once all of these preparations are completed, then the excavation can begin.

In the Field

A typical day begins with breakfast at zero-dark-thirty (or about 4:30 am) followed by travel to the site. The team arrives before sunrise in order to make progress photos in the warm glow of the pre-dawn light. The first order of business is to “brush up” the square (remove foot prints and any dust that settled overnight so the square looks clean and the rocks and any architecture will be clear in the photo). While waiting for the photo, the Square Team prepares the pottery pail with the appropriate tag, places the counter by the sieve for counting gufahs of soil, prepares the bone bag, and updates the Locus Sheet with Pottery Pail Tag numbers. Also, the Square Supervisor may discuss with the Field Supervisor the planned agenda for the day’s excavations. Once the progress photos are taken, the Square Supervisor records the photo numbers on Locus Sheets for all the loci visible in the photo.

Now that all the daily preliminaries are out of the way, excavation can begin. The actual digging usually does not involve any tools larger than a hand pick or a trowel. Most of the soil is removed by scraping it up with a trowel into a dustpan and then dumping it into a guffah. The filled guffah is taken by a local worker to the sieve where the soil is sifted through a screen in order to find small objects.

As the guffahs fill with soil, the Square Supervisor has several concerns in mind. First, the Square Supervisor is mindful of the local workers. Are they keeping count of the number of guffahs of soil removed? Are they carefully looking for small objects as they sift the soil? Are workers from another square mistakenly using the wrong sieve? If so, there is a great risk of data contamination, i.e., potsherds placed in the wrong pail. Second, the Square Supervisor is concerned about the work in the square. Is the excavation being done carefully, so to articulate objects, features, and architecture? Is there a texture or color change in the soil, requiring the start of a new locus? Is all the data being properly and promptly recorded? These concerns are not as burdensome as they may sound. Good training for the Square Team at the beginning of the season helps each team member know his or her role and helps the entire operation work smoothly.

Work continues up to “Second Breakfast” (around 9:00 am) when the team stops for a break. By this time the sun is already hot and beating down, promising another mirror day of all the other, very predictable days of summer in the Jordanian desert. The ever mindful Square Supervisor begins to push water consumption by the crew. Heat and low humidity takes a subtle toll on those who do not drink plenty of liquids.

After breakfast, excavation work continues for another 3 1/2 hours or so. Around 12:30, the focus becomes finding a good stopping point and gathering all the tools, equipment, pottery pails, etc., that need to be brought in from the field. When the square is cleaned up and tools secured, the team “heads home” (back to the hotel or wherever they are staying) with the yearning for a good bath and a tasty afternoon meal. However, before the bath and meal, the pottery pail is filled with water so the sherds can soak awhile before they are washed later in the afternoon.

Afternoon… and the Work Continues

Afternoons provide some rest and leisure time (an opportunity to do laundry, write letters, or take a nap). However, at some point in the afternoon or evening, the Square Supervisor must attend to the Field Notebook. He/she looks over notes from the field that particular day to see if all the information is recorded clearly and correctly. Also, this is the time to look for missing information or the time to plan for the next day’s excavations. At this time, the Square Supervisor writes daily reports, reports that chronicle the day’s excavations usually sorted by loci. Once a week, the Square Supervisor writes a weekly report, using the daily reports as a guide, recording the excavation progress for that week. Weekly reports also are sorted by loci. The daily and weekly report forces the Square Supervisor to consider the evolution of strata in the square.

At some point in mid-afternoon, pottery reading commences. The Square Supervisor is at the pottery reading table early to ensure the previous day’s pottery is laid out in an orderly manner on the table and ready to be read by the pottery experts. As the experts, date and categorize the pottery pieces (by type), the Square Supervisor records the “readings” in the Field Notebook on the Pottery Reading Sheets and on the Locus Sheet that corresponds with the loci recorded on the Pottery Pail Tag. This information gives the Square Supervisor some idea of the dating of loci. For more information on pottery reading and the significance of pottery in dating strata, see “Pottery from the Ground Out”.

At the time of pottery reading, other team members are busy washing the potsherds brought in from the field that day and then placing them in mesh bags (with the Pottery Pail Tags) so the sherds can dry. The pottery will be read the next day. A good Square Supervisor will help wash pottery if time permits.

Evenings

Work in the evenings will depend upon what the Square Supervisor did in the afternoon. If the Field Notebook is up-to-date, then all that needs to done is gather the next day’s supplies for field. Otherwise, the Square Supervisor works on the Field Notebook.

And finally, it’s bedtime and a chance to rest up for the next day.

End of the Season

After several weeks of excavations comes the time of closing down the square for the season. Usually, this process starts about five days or so before the time the team permanently departs from the site. The first order of business is to make a final Top Plan of the square. (To see a sample Top Plan, click here.) This Top Plan will be extremely important not only for stratigraphy but also to mark where the excavation stopped. The next season in the square must start at the same point, which may be under several centimeters of soil (wind-blown sediment) by the time the Excavation Team returns.

Next, the Square Supervisor’s attention turns to balks. If not done already, the balks must be trimmed so that they are vertical and smooth. A clean balk allows one to better see each locus.

Balk drawing

Then, each balk must be drawn to scale, with indications of each locus visible in the balk drawing. This information is critical when looking at the relative chronology of the square.

In addition to balks, one must also draw all architecture (each exposed vertical surface) and any other vertical feature within the square. The drawing process is tedious and very time consuming but the data is essential for the Excavation Team’s future analysis of the square.

When all the drawings are complete, the square must be cleaned up for final photos. All dust is brushed off every feature so that all features will be clearly visible in the photos. Also, all traces of the team’s activities are removed, such as footprints, balk strings, tools, etc.

After final photos are made, the Square Supervisor will place indicators (plastic or burlap bags) at various places on the bottom of the square. These indicators mark the bottom of the square and serve as a reference when excavations begin again the next season. The location of each indicator is marked on a copy of the final Top Plan so that they can be easily found the next season. Then, some of the soil from the sieve is placed back in the square to cover the indicator and to protect the bottom of the square. If the square has been completely excavated, the square may be completely filled to prevent erosion and to restore the integrity of the site. Whichever the case, the square is now prepared for the dormant period until the next excavation.

Although out of the field at the end of the season, the Square Supervisor still has a few concerns. The Field Notebook has to be thoroughly checked for accuracy and missing information. This process includes getting object numbers from the Object Registrar. (Each object found at a site is given a number. These numbers must be recorded in the Field Notebook.) Once the Field Notebook is complete, it is turned over to the Field Supervisor.

After completing the Field Notebook, the Square Supervisor may also write up a brief chronology and analysis of excavations in his/her square. This analysis will be integrated into a larger report written by the Field Supervisor.