Bedouin of the Karak Plateau in Jordan

Dr. Murl Dirksen

Typical Bedouin summer camp on Karak Plateau

Numerous Bedouin groups occupy the Karak plateau in central Jordan (see map). The western border of the Karak is the Dead Sea and to the east is the Sahara Desert. In addition to these nomadic Arabs of the Karak Plateau, permanent residents include both Christian and Muslim villagers that represent a traditional shepherding and agricultural way of life that has existed for thousands of years, but they also exhibit characteristics of the rapid modernization of rural areas throughout the Middle East.

The Karak area has a long history of human occupation. Numerous archaeological sites in and around al-Karak date back to the early Bronze Age, 3300 –2000 B.C. Proximity to the harsh environment of the surrounding desert and lack of water has contributed enormously to the value of this small area of arable land where the Bedouin, the nomadic people of the desert, spend their spring and summer months in interaction with the settled people of the Karak Plateau. Nevertheless, other Bedouin reside on the plateau all year round and occasionally move only a few kilometers because of their migratory agricultural work or to seek better grazing.

The various Bedouin groups include the nomadic tribes from the Sahara Desert, the traditional Jordanian Bedouin that winter in the south and spend the spring and summer in the central and northern parts of the country, and the displaced refugees from Palestine. There are also several groups of gypsies that reside in the area. Each of theses groups are distinct having their own migration patterns and subsistence patterns.

The term “Bedouin” is a nebulous concept. It most commonly refers to moving Arabs. A great exploration into the various facets of the term is presented in an article by one of the members of our research team, William Young (see bibliography). Comparing Bedouin to the term “farmers” in North America gives one a bit of a reference point for the concept. The farmer of the past is not the farmer today although one can still find examples of the family farm. The image of “farmer” exists more as romantic national icon than a real thing. To Middle Easterners, Bedouin holds a similar emotional response. It is something of the past and not the present and those that are holding to this way of life in the present are given little respect and sometimes shunned.

The present day Bedouin tend to be poor, barely surviving, without much education, and not extremely loyal to the government. Government policy has favored the settled populations and discouraged nomadism and semi-nomadism. The Bedouin are a marginalized population.

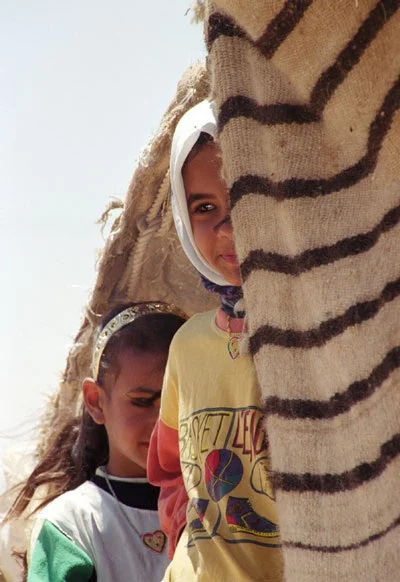

Bedouin sisters

Hired Bedouin herder collecting village animals

Many of the villagers of Karak began the transition from a totally nomadic way of life as Bedouin to a settled village life at the turn of the 20th century yet maintain some of the traditional customs. Numerous village families own herds of sheep and goats but hire Bedouin to do their herding. In addition, settling on the Karak Plateau has afforded the villagers the opportunity to engage in rain fed dry land farming; consequently, if the grain is poor or after a good harvest the stubble can be leased for grazing to the Bedouin. There are numerous situations to bring the Bedouin and villagers into interaction.

Many of the traditional ways are still maintained by the Bedouin. Milk processing, weaving of rugs and tent cloth, and shepherding are basic to their way of life. Women and children are responsible for maintaining the family herd and the making of cheese, yogurt and butter. Men are engaged in business matters, hauling the water, interfacing with government agencies and wage labor. Marriages are polygamous and arranged. Families tend to be large and incorporated extended family members.

The following is a survey of the nomadic people of Karak who graciously invited us into their tents, generously served us coffee and tea, and spent long hours sharing their desperate personal stories. They allowed us to intrude into their private space with notebooks, tape recorders, digital cameras, and unending questions. We hope that this study will help the world better understand the diversity of Bedouin life in Jordan, their courageous struggle as an under class, and their effort to maintain their nomadic way of life while adapting to the modern world.

Odee’s mother (front) and wife (left)